There’s nothing wrong with a little ‘friendly’ competition, but when did we lose the plot?

On the cusp of 2024, I found myself doom scrolling on The App Formerly Known As Twitter when I came across a clip of Soulja Boy dissing Blueface on Instagram live. The “Bussdown” rapper had apparently claimed that he could beat the “Crank That (Soulja Boy)” rapper in a Verzuz battle. I chuckled at the prospect of a potential beef between the two rappers and continued my scroll down the void of unscrupulous “hot takes” and repurposed TikToks meant to mine likes on the now-monetized “X.”

Some days later, another headline popped up during my doom scroll, this time stating that Soulja Boy was ready to “crash out.”

“Let’s die,” he remarked. “Let’s meet up and die. Let’s die. ASAP!”

I had neither the awareness nor the ability to appreciate some of the beefs that arose during my childhood in the early 2000s, such as Nas versus Jay-Z or 50 Cent versus…everyone, but I remember when Drake released “Back to Back” in 2015, a diss track aimed toward Meek Mill after the “Dreams & Nightmares” rapper alleged that Drizzy had a ghostwriter. I also remember when Pusha T dropped “The Story of Adidon” in 2018, revealing that Drizzy had a son named Adonis. More recently, I was able to witness Megan Thee Stallion release “Hiss,” a diss track that sent shots toward a number of rappers but seemingly resonated most with Nicki Minaj, who released “Big Foot” a few days later. That will certainly be an experience that I will never forget.

Competition has and always will be a key part of hip-hop, not because it’s a dire necessity but because it elevates the game. When Kool Moe Dee went up against Busy Bee Starski in 1981, he showed that hip-hop could do more than rock your body. Mastery of lyricism could help attain legendary status that’d be recognized across generations. In conjunction with some friendly competition, it can both showcase skills and boost relevance. With “The Bridge Wars” of the late 80s– a legendary feud between Boogie Down Productions (BDP) of the South Bronx and the Queensbridge-based Juice Crew – the two crews were working to set the record straight on whether or not Queens or the Bronx birthed hip-hop. In the midst of this “war” came another one, this time heralded by a then-14-year-old Roxanne Shanté. A protégé of Juice Crew co-founder Marley Marl, she recorded her first song, “Roxanne’s Revenge” as a response to U.T.F.O’s “Roxanne, Roxanne,” sparking what would later be known as “The Roxanne Wars.” Over the years, different numbers have circulated to indicate how many “Roxanne Response Songs” were recorded, but that number falls somewhere between 30 and 100.

As hip-hop entered its “Golden Age,” crews and rappers feuded– some for the sake of notoriety and others for the sake of simply proving they were the best. In many cases, rappers feuded because one accused the other of “biting” their style– think Kool Moe Dee versus fellow Queens cat LL Cool J.

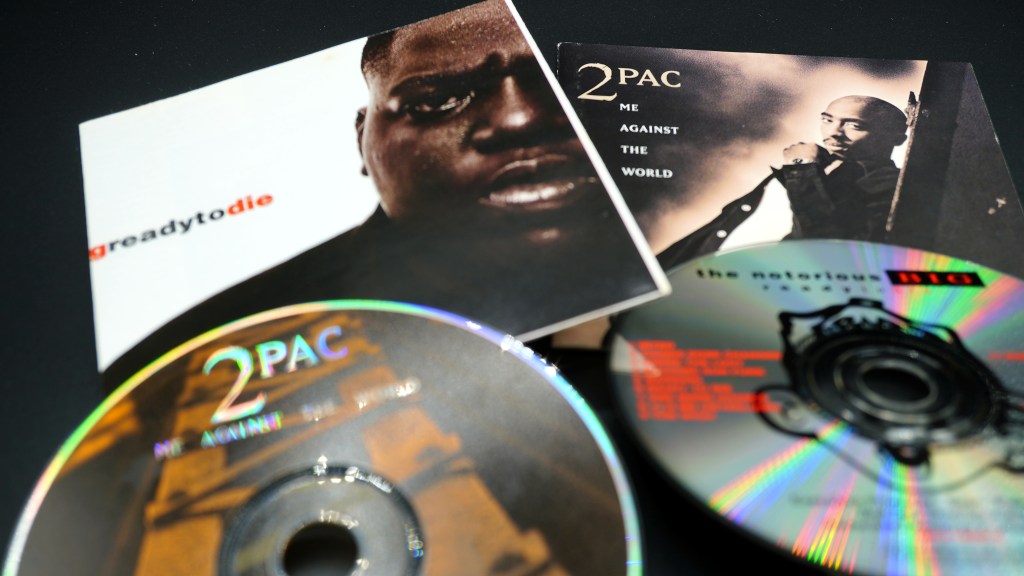

But something changed with Biggie and Tupac.

The two rappers were born in New York City, but they repped opposite coasts at the height of their short-lived careers. They were initially friends who respected each other’s craft, but things turned sour in 1994 when Pac was shot five times in the lobby of Times Square’s Quad Recording Studios, according to Biography. Pac believed that Biggie and Diddy, the founder of Bad Boy Records, had something to do with this attack. Once Suge Knight signed Pac to Death Row Records, the rappers and their parent labels continued feuding.

Biggie would go on to release “Who Shot Ya?” in 1995. Though it was originally recorded a year prior for Mary J. Blige’s “My Life” album and shelved, Pac saw its release as confirmation that Biggie was, in fact, involved with his brush with death. He responded with “Hit ‘Em Up” in 1996, sending direct shots at Biggie, Bad Boy Records, and R&B singer Faith Evans, who he claimed to have slept with. Things would continue to escalate until both rappers were gunned down six months apart. Their deaths have yet to be officially solved.

Embed from Getty ImagesThis isn’t to say that all feuds up to that point were always “friendly,” nor is this to say that Biggie and Tupac were the first well-known rappers to face death. In fact, DJ Scott La Rock, a co-founder of BDP, is often cited as one of hip-hop’s first major losses. He was gunned down in 1987 after attempting to deescalate a heated altercation. He was only 25.

Scott La Rock’s death, along with the death of a young fan at a Public Enemy and BDP concert, would temporarily halt the feud between BDP and Juice Crew while simultaneously inspiring BDP co-founder KRS-One to start the “Stop the Violence Movement.” A collaboration amongst various East Coast rappers– including Doug E. Fresh, Just-Ice, Heavy-D, and MC Lyte– the collective released “Self Destruction” in 1989 and donated the proceeds to the National Urban League, an organization that has empowered Black and other marginalized communities since 1910.

This was a monumental effort, yet the violence in the Black community, particularly amongst those enthralled in hip-hop, did not stop. As the genre arose, so did the tensions amongst rising MCs. Suddenly, hip-hop was no longer being upheld solely by the East Coast. Suddenly, rappers were speaking on everything from the bling they rocked to the violence they faced and, at times, enforced onto others. Suddenly, it wasn’t just the prospect of lyrical slaughter that became associated with the culture. Legitimate slaughter was fair game, too.

Hip-hop itself is not to blame, as the culture was not founded upon violent principles, nor were there inherently violent themes overwhelmingly present at the helm of the genre. In fact, a number of rappers have condemned violence, even if their lyrics at times take on a violent tone. The larger problem at hand is a more systemic one.

Society stands still when Black men and women face violence and death, regardless of whether or not they are famous.

In the nearly 40 years since the killing of Scott La Rock, hundreds of rappers have been killed. I was able to find one list containing approximately 860 names of rappers who have died since 1987. While causes of death range from shootings to health-related issues and overdoses, I was able to count over 500 who were shot and killed. An overwhelming number were 30 and under.

Not all of these deaths can be attributed to rap beefs, but the amount of violent deaths in hip-hop remains a huge problem. If it were white country artists or rock and roll stars dying at such alarming rates, there would likely be a much more concerted effort to address the violence.

Rappers can form short-lived supergroups that uphold anti-violence; they can tell kids to stay in school, get off the streets, and invest in themselves to see a future past 30. But when there’s nothing being done at a systemic level to address legitimate marginalization–the conditions that make violence a viable option– these efforts stand in vain.

Hip-hop has changed the lives of numerous Black men and women, but many lives have been lost or nearly lost– not in the name of “hip-hop” but in the name of a larger white supremacist system that sanctions that loss of life. It’s much bigger than any feud between two rappers.

As a lover of the genre and what it represents, I have always enjoyed the prospect of a little rivalry between two MCs, but at what point do we stop allowing friendly competition to turn into death matches? At what point did “Roxanne Wars” become “Stan Wars” that result in doxxing and the disclosure of grave sites? At what point do we stop letting rap beefs become about anything more than the music?

I’d like to think that this could change, especially with the recent events that have ensued. Clearly, there are still rappers who know how to send their shots via lyrics. But it often seems as though people are too comfortable letting the music be an afterthought in these feuds.

If left to the powers that be, it might be militarized police forces and criminalized rap lyrics that will be dubbed the solution. But maybe we aren’t too far gone as a culture. Maybe it falls on listeners and fans of the medium to disengage with those who deliver soliloquies via social media platforms and rally their goons as opposed to leaving it all in the booth. Maybe it falls on us to decenter our idealizations of the people we don’t know and recenter the music– the reason they are relevant in the first place.

Otherwise, the plot remains lost, as do the lives of the rappers we aim to love.

Leave a comment