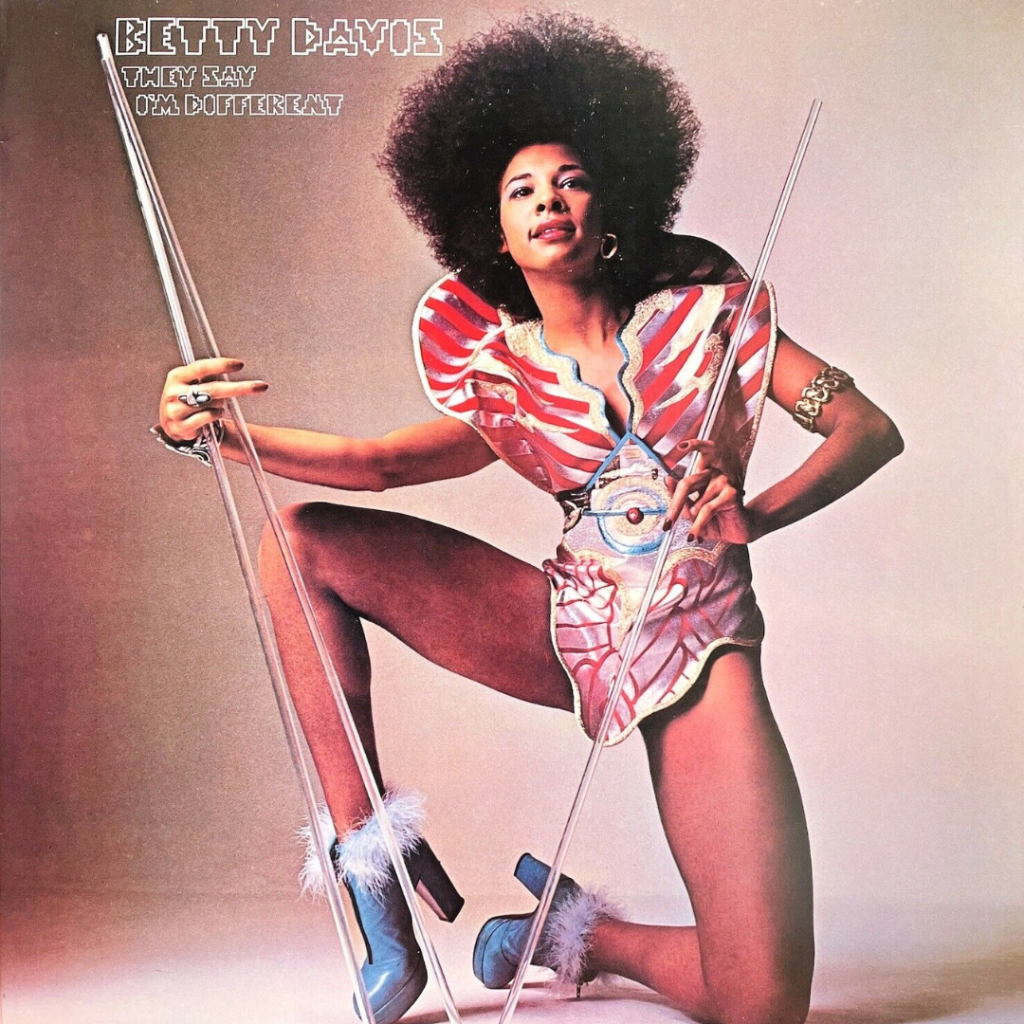

An ode to the “Queen of Funk” and the audacity of her sophomore album.

This note serves as a formal petition to the folks over at Merriam Webster: the definition provided for the word “audacious” does not suffice.

Sure, phrases like “intrepidly daring,” “marked by verve,” and “contemptuous of decorum” could provide a fair level of understanding.

Yet, a word that seeks to communicate such zeal for boldness needs a stronger, more tangible representative. One whose impact can be felt, seen, and heard across generations. One whose influence lives past words on paper.

Betty Davis should be that representative. Her legacy is as audacious as it gets.

Born Betty Gray Mabry, she was born in Durham, North Carolina, brought up in Homestead, Pennsylvania, and relocated to New York City as a teenager, where she sustained herself as a Fashion Institution of Technology student and magazine spread model.

She’d eventually become close with the likes of Jimi Hendrix and Sly Stone while also becoming more and more acquainted with the music scene.

Betty Mabry would get her start in showbiz by writing “Uptown (To Harlem)” for The Chamber Brothers in 1967, and a year later, she earned the last name Davis after a short, tumultuous marriage with famed trumpeter Miles Davis.

“Every day married to him was a day I earned the name Davis,” she claimed in the 2017 documentary, “Betty: They Say I’m Different.”

But she earned more than this name, procuring both a title as the “Queen of Funk” and cementing her place as one of the most prolific artists to come out of the 70s.

In 1974, Betty Davis gifted us with her sophomore album, They Say I’m Different. 50 years later, it is clear that the 8-track LP has lived up to its title.

She was different, donning her southern roots and sexual prowess with pride despite society’s ever-present demand that Black women abide by respectability politics.

Black American culture experienced a sort of renaissance in the 1970s, with feats such as the “Natural Hair Movement” and programs like Soul Train pervading mainstream Black culture, but this did not mean that Black people– and particularly Black women– were not expected to maintain a particular persona on and off-stage.

Davis, in all of her audacious glory, never let this stop her from producing music that she described in one word– raw.

Embed from Getty ImagesFrom the moment she released her debut album, Betty Davis, in 1973, she made it clear that game was her middle name, and it wasn’t love that she was vying for– it was pleasure. She was unafraid to speak of the pleasure she aimed to both give and receive. But on They Say I’m Different– her first time both writing and producing on her own– her role as a would-be seductress is even more refined.

On “If I’m In Luck I Might Get Picked Up,” the opening track on Betty Davis that at the time of its release was banned from the radio, she claims to be wild, crazy, and nasty. Yet, these attributes are not framed as a sure-fire way to take hold of a lover. “Fanny wiggling” aside, her efforts are positioned as something that might get her picked up.

“Will you take me home? Baby please,” she pleads, inferring that she is not the one in control here. Her exploits could be successful if she’s in luck, but it’s up to that unnamed lover to make the final decision.

This differs greatly from “Shoo-B-Doop and Cop Him,” the opening track on They Say I’m Different.

In this song, there’s no question as to whether or not she will get to “shoo-b-doop all night.” The man is fine, and she knows exactly what she wants.

“I’m gonna love him funky free and foolish,” she proclaims. “I’m gonna do my best and try hard to get him.”

It’s not up to him. There’s no need to prove that she’s worth the experience. Sex is not framed as something that she hopes will be done to her, but rather an experience that will be done for her– she’s the one in control here.

Her power is even further asserted on, “He Was A Big Freak,” where she speaks on the preferred kinks of an unnamed lover, namely his affinity for being whipped with a turquoise chain.

Where game was her middle name, pain was his– and he used to really dig it.

On They Say I’m Different, Davis is all about grasping onto her power, and there’s no shame in her game.

“Your Mama Wants Ya Back” details her desire to get her man back– a funky “Spin The Block” anthem, if you will– while “Don’t Call Her No Tramp” speaks to the tendency to slut-shame women who are unapologetic in their sexual exploits.

“…when she leaves you ’cause she don’t need you no more and you feel like a fool, don’t you call her no tramp,” she declares. You can call her superficial, you can even call her a “chic shakin’ hustler,” but she’s no “sleazy skive.” You cannot shame a woman who moves unapologetically.

Betty Davis never claimed to be a “feminist,” but her music championed the sexual agency of women in a way that aligned with the second-wave feminists of her time. Though the feminist movement had work to do in terms of its inclusion of Black women and other women of color, there were certainly commonalities surrounding the idea that the sexualities of women should be acknowledged and even catered to rather than repressed.

But Davis took this to another level.

She made sexual prowess and agency funky, donning her Afro as she gyrated in hot pants and thigh-high boots.

She shrieked and sang in low, raspy purrs as she detailed raunchy exploits and how badly she wanted “papa.”

She wasn’t afraid to be seen as a “Nasty Gal,” and in 1975, she would release an album of this same name.

On the album’s title track, “They Say I’m Different,” she speaks of slopping the hogs every morning and eating chitlins. She speaks of her great-grandmother’s love for Elmore James while her great-grandfather got down to Jimmy Reed and B.B. King. She came up on the blues, and it is because of the blues that she could groove.

Her upbringing was different, and to many, her music and overall image were strange. But she was sweet to the core. That’s how she got rhythm.

By the album’s end, on “Special People,” she speaks of a willingness to provide love and care for a special person with troubled, weary eyes.

“…when I think about you, torn and tortured, you look so free, they can’t see you chained,” she proclaims, offering a willingness to be there for this person.

Yet, this can equally be seen as a declaration of love and support to herself.

From the violence she faced in her marriage to Miles Davis, to the harsh judgment she faced for her provocative music, Betty Davis’ life was far from perfect.

But she was special. She was unwilling to compromise her artistry to appease the mainstream and the label heads who wanted her to maintain a tamer image. She could not be chained.

Davis was not as commercially successful as other funk divas like Donna Summer and Chaka Khan, but she left an imprint that’s lasted in the years to follow her debut.

Musicians like Erykah Badu and Janelle Monae cite her influence directly, but any artist who has dared to detail their love for pleasure has Ms. Davis to thank for breaking the mold and, to some extent, creating one of her own.

In her documentary, she speaks of a crow whose essence followed her from Durham to The Big City. While crows are often said to represent death and misfortune, this crow was a companion of sorts, a reminder of a life in which her worries could be easily quelled by the music of T-Bone Walker and Bessie Smith and Big Momma Thornton. It was Crow who stayed with her through turmoil and helped her put it all in the music.

“Crow hid my pain, so I wrote and sung my heart out,” she said. “Three albums of hard funk. I put everything there.”

She completed her final album, “Is It Love or Desire,” in 1976, though it would remain unreleased until 2009. After the death of her father in 1980, she mostly disappeared from the music world and lived a quiet life back in Homestead until her own death in 2022. She was 77 years old.

A funk diva through and through, Betty Davis was different– wholly and unapologetically.

It is thanks to her comfort with being different and her audacious nature that artists who champion liberation (sexual and otherwise) are now the norm.

“Being different is everything,” she said. “It is the way forward.”

And it is forward that we will continue to go. Sho’ Nuff.

Leave a comment