A reflection on why there’s no room for coddling in the name of artistic growth.

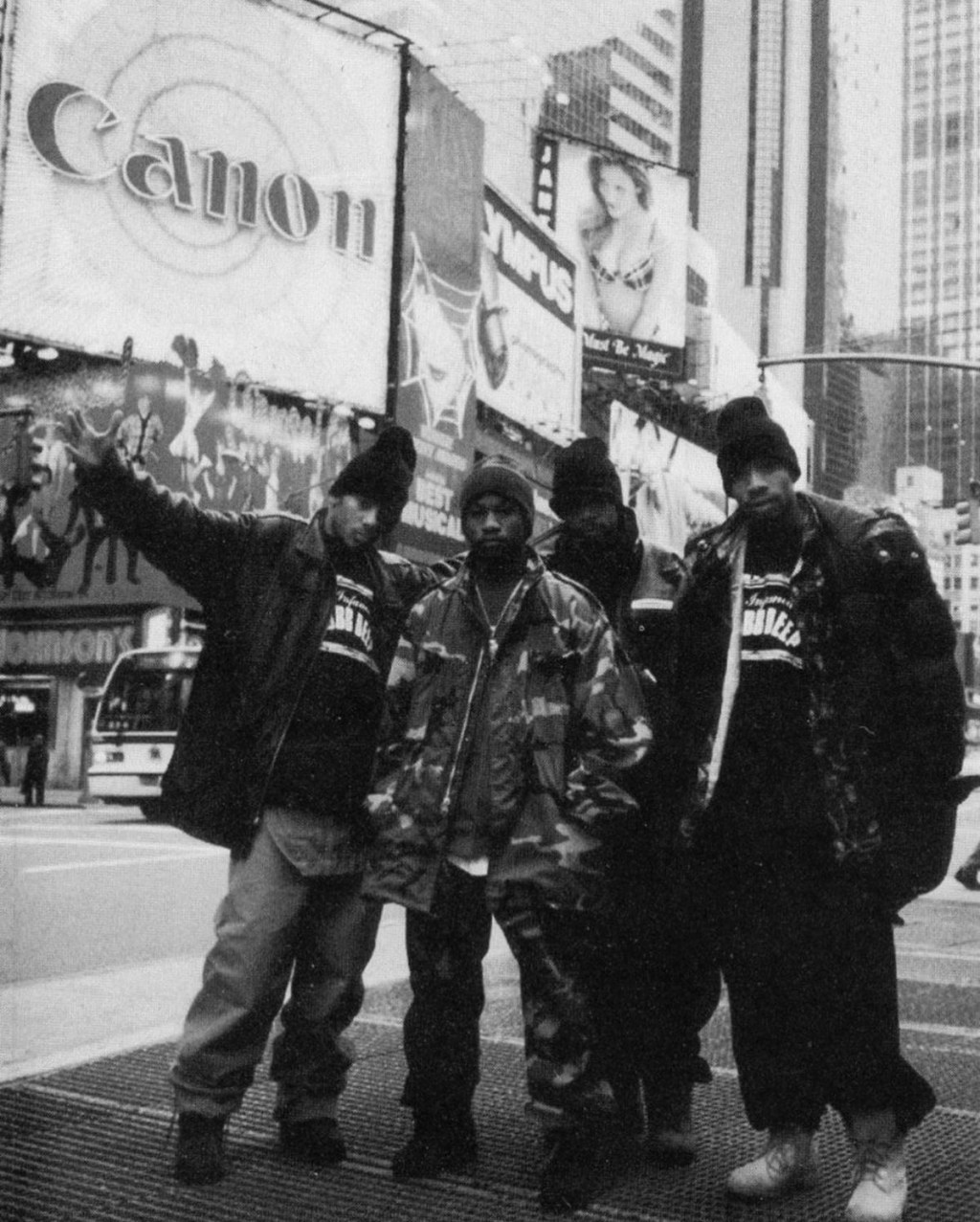

By 1995, these two Queens cats had something to prove.

They were only a couple of years removed from the release of their first studio album, which marked an early setback in the duo’s eventual rise to success. A 14-track LP, the 1993 project– which featured recordings from their late teenage years– showcased the duo’s youthful rawness and talent. It was even supported by two singles, one of which charted on Billboard’s Hot Rap Singles at #18. But they hadn’t yet refined their sound or their lyrical story, and it showed. The LP failed to reach commercial success and ultimately got them dropped from their label.

So in 1994, they went back to the drawing board. Inspired greatly by Nas’ Illmatic, particularly his storytelling, they worked closely with Schott Free and Matt Life– the album’s executive producers– to improve their sound. Q-Tip would eventually come on as the album’s mixing engineer, helping re-do beats and revamp the drum programing on a few of the songs.

In late April of 1995, the album would come out and be met with much acclaim.

Detailing the realities of street life– including drugs, prison, and murder– the project’s eerie undertones are assisted by classic soul and jazz samples (such as Al Green’s “I Wish You Were Here” and Grover Washington, Jr.’s “Black Frost”) and some of the illest hi-hats. It’s dark, but it’s hard. And nearly 30 years later, it’s a certified classic that is recognized for its contributions to East Coast hardcore rap.

The album, The Infamous by Mobb Deep, was certified Platinum in 2020, and it’s an auditory treat from start to finish. It goes so crazy that folks often forget about their debut, Juvenile Hell, altogether.

But that’s what happens when “failure” has consequences.

Raw talent can get you places, but in the pre-streaming era, it could only get you so far.

You couldn’t rely on virality, “bad press” turned good, and TikTok snippets to remain relevant. If the sh*t didn’t bump, you were done for–unless you were hungry for it. Then, you could potentially salvage your reputation and sales.

But the problems of the past are different than the problems of the present, and it’s seen in everything from the quality and length of the music to the manner in which it is rolled out.

Performers of the streaming era are tasked with converting streaming numbers and social media virality into tangible income– all while accommodating consumers with shortened attention spans and an overload of “content.”

While this doesn’t necessarily mean that the music has gotten worse on a grand scale– there is still plenty of good music out there– it is just not the same as it once was for a large number of non-legacy acts.

Album rollouts are not nearly as expansive, for example. Where performers of the past could book promo slots via TV, radio, and print magazines, modern-day performers don’t have as many options. Podcast appearances and online magazine features are certainly viable means of getting the word out, but the vast majority settle for a cleared-out Instagram feed, a teaser video, and an album or single announcement via The App Formerly Known as Twitter.

The music itself seems to be getting shorter and shorter, with a large number of chart-topping singles standing at less than three minutes, according to The Washington Post. This isn’t too alarming, as the average lengths of songs have always fluctuated due to the technologies that were available at different periods of time. Yet, there seems to be a clear demand for shorter songs– hence the increase in artists who release sped-up versions of their singles.

Nevertheless, shorter songs lead to shorter projects and shorter moments of relevance. Lots of newer artists vie for mixtapes and EPs– which, once again, is not a new concept– but full-length albums don’t always feel as…full.

The music itself and the storytelling could be solid as ever, but some albums just feel like an EP wearing a pair of platform sneakers, meaning that there’s only an illusion of added length. Once you reach the end, you realize that the extra two or three songs are either exceedingly forgettable or are remixes of an already-released single, and if you removed those songs from the project, the “album” would just be an EP.

Shoe comparisons aside, all of this is said with the full awareness that good music is still out there– even if it is condensed in a seven-song EP or a 10-song LP. In fact, seven great songs is much better than 17 songs that are mid.

Album rollouts might not be as expansive across the board, but Vince Staples brings up a fair point in a recent interview with Andre Gee of Rolling Stone. On the promotion of his latest album, Dark Times, Staples told Rolling Stone that there’s no real reason to engage in traditional means of album promotion if people are no longer required to buy physical renderings of the music. If all that we really need is our phones, then “you might as well just give people the opportunity to digest it quickly,” he said.

There are plenty of artists who are still hungry for it, continuously working to improve their music while also utilizing shortened attention spans and social media to their advantage.

But there aren’t as many consequences for objectively failing or simply being…bad.

And that falls on us.

It often feels as though an artist could release two minutes and 13 seconds of them repeating the same three words over a looped sample from the late 90s and still go viral as long as it is accompanied by an equally ridiculous, yet visually stimulating, video.

More often than not, stans and other members of the “chronically online” crowd do not demand quality, or even common decency, from the people whose music they champion. And if people can come to the general consensus that something is bad, there will still be those who act like they are paid to relentlessly defend the artist (not the music, which should be the focus). Criticism is almost wholly discouraged, as any expression of discontentment will get you berated for being a so-called hater.

Folks are much more content by the idea of passing around participation trophies for a good effort rather than handing out some real prizes for a great output.

Music isn’t the same anymore, but it shouldn’t be. As the tides change, artists should refine their approach to consumers. However, some consumers seem to have trouble reciprocating this adaptability. People are far too comfortable staying within a singular box, and more often than not, they demand that their favorite artist does the same thing.

As crazy as the concept seems, there is so much good music beyond what the algorithm on your preferred streaming service suggests. Your favorite artist can, in fact, do wrong in some capacity. This does not mean that folks should resort to straight up beratement, but it’s important to recognize both the good and the bad elements, as they can co-exist together.

More than anything, we have to realize that “infamous” moments sometimes come with consequence.

Prodigy and Havoc of Mobb Deep made their potential clear on their debut project, and there are likely a number of fans who liked the album back then and find it solid now.

But there was no one to hold their hand or give them an “A For Effort” after Juvenile Hell initially flopped. They had to work hard to reach that legendary status.

And while failures to reach commercial success or “bad” music are not sure-fire prerequisites for growth, it damn sure doesn’t come from coddling.

In this day and age, access to music that spans all eras and sounds is nearly endless. Artists can rely on a number of methods to distribute their music and ensure that it has a place in the mainstream.

But this doesn’t mean that demanding more, particularly in terms of the music’s quality, is in bad taste. It doesn’t make you a hater if it comes from an earnest place of wanting to see someone reach their full potential.

There’s room for everyone, but that doesn’t mean they should all be occupying space– not until it’s clear that their spot has been earned.

Leave a comment