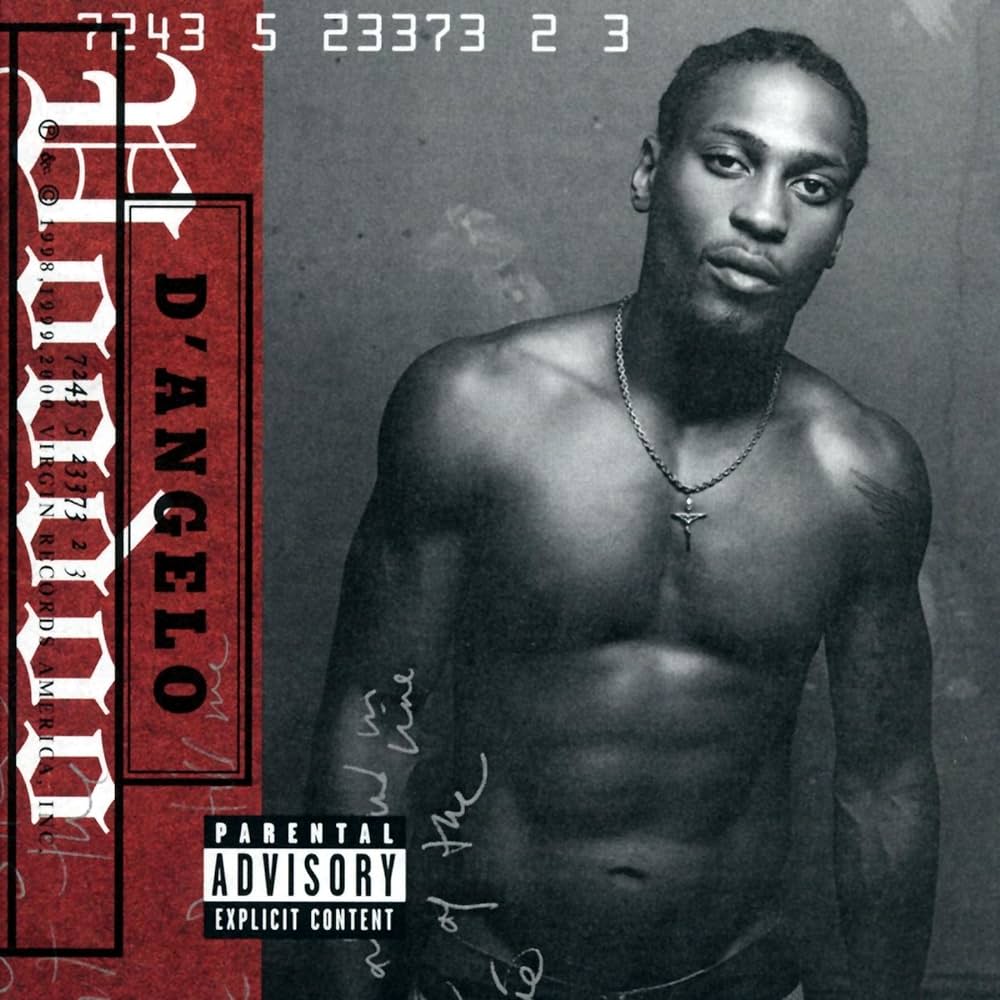

D’Angelo’s “Voodoo” was released on January 25, 2000. 24 years later, How Does It Feel?

There’s something that most if not all great artists have in common, and it is the perpetual strive toward perfection.

It is often said that perfection is an illusion that, when sought after, does nothing but hold you back. And maybe there’s some merit to this premise. Maybe the impossible task of attaining perfection is why Michael Eugene Archer, or D’Angelo, has only released three projects in the nearly 30 years since his debut. Maybe this unattainable feat, coupled with concerns of being as great as his musical forefathers like Prince and Marvin Gaye has, at times, left him feeling cemented.

But maybe perfection is less about achieving a truly perfect outcome and more about the process – the restless nights and discarded tapes and crumbled pieces of paper. Maybe it’s through this strenuous process that greatness, regardless of its alignment with “perfection,” is truly achieved.

And D’Angelo’s legacy is nothing if not a testament to how dedication to your craft can sustain greatness and longevity.

Speculation aside, it’s clear that the mind, body, and spirit of the singer, multi-instrumentalist, and songwriter stood fully present as he was crafting the experience that is Voodoo, a 13-track LP that is often heralded as his Magnum Opus. (But to be fair, most fans of the singer can easily point out why any of his three projects can be considered his best work.)

The singer is often recognized for his contributions to the genre of neo-soul, though the experience of Voodoo is not bound to any particular genre. When it comes to “neo-soul,” the term coined by record label executive William “Kedar” Massenburg, few artists who technically fall within that category even claim it, including D’Angelo.

“I never claimed I do neo-soul,” he said at a lecture part of the 2014 Red Bull Music Academy Series, according to Guardian. “When I first came out, I said, I do Black music.” And Voodoo is nothing if not a love letter to Black music.

Soul steers the ship, functioning as an omnipresent force that guides you through themes of love and love-lost, of corporate greed and its resulting sin, and even through the power of rootwork– which is unsurprising given the experience’s name. Yet it is far from the only passenger. It’s the influences of hip-hop, funk, jazz, and even conga that help comprise the fabric of Voodoo.

D’Angelo, supported by contributions from the likes of ?uestlove, Raphael Saadiq, Charlie Hunter, James Poyser, Angie Stone – his son’s mother – and more leads you to levels of enchantment that can only be achieved via intentionality and a true love for the craft.

The first track, “Playa Playa,” sets the tone by challenging fellow artists to bring their A-Game. Though this is expressed via references to basketball – “shoot your best shot” for example – it’s clear that he aims to claim the title of number one. It’s lined with a boastfulness that, 24 years later, has proven to be more than warranted.

Each song bleeds into the next with transitions as effortless as the singer’s croons, not to mention the fact that the experience feels like a masterclass on song construction. As each instrument makes its way onto the track, it feels like you are sitting in on one of the many sessions that took place at the legendary Electric Lady Studios, like you are hearing the songs come together in real time.

For many, the biggest standout of Voodoo is none other than the famed “Untitled (How Does It Feel),” a symphony of lust and intimacy personified. Though it ends abruptly– due to the tape running out– the ode to Prince’s Controversy era is certainly deserving of all its flowers.

The video is where most lost and continue to lose their cool, as there’s little left to the imagination. His labeling as a “sex symbol,” and his discontentment with this status, would lead to a 14-year hiatus after the completion of the Voodoo tour. But 14 years away from the limelight gave us Black Messiah, a project with “Really Love” and “Another Life” – so the time lost wasn’t a complete loss.

But my personal favorite would have to be “One Mo’Gin,” a song that marks the second half of the experience.

The ballad slowly builds up with light chatter that leads into a beautifully mastered take on what happens when past lovers cross paths again– how they remind you of the changes that have occurred since your encounter, the desire to be in each other’s arms again, and the inability to find a lover of the same caliber.

“Never bumped into your kind before or after,” he laments, accompanied by vocals stacked so flawlessly that you can’t help but transcend– and he himself is the kind of musician that, despite his influence on artists to come, has yet to be perfectly copied. He is the kind we haven’t bumped into, neither before nor after his debut in 1995.

As dream hampton states in her 2000 Vibe cover story, this “Soul Man” was “virtually peerless.” She writes that, in reference to D’Angelo’s spirit, rapper Common once said, “It comes from another dimension.” And Vodou itself, a term derived from the Fon and Ewe languages of West Africa, is all about spirit. The idea that everything is spirit. And spirits, whether seen to the visible world or not, are meant to be served.

Like Vodou, an Afro-Haitian religion with ties to the traditional religions of Central Africa, West Africa, and even French Catholicism, Voodoo is the result of African diasporic transcendence. Not only is the experience rooted in spirit, but it serves various facets of the spirit. Spirits of love and sensuality and happiness and ancestral connection. It’s no coincidence that the project holds this title, nor is it coincidental that the final track– dedicated to his son– is called “Africa.”

Nevertheless, Voodoo had something for everyone. For the hip-hop heads. The soul lovers. Even the sinners who shook it “Left and Right” in the club on Saturday but still sought to “Send it On” in church Sunday morning. You didn’t have to understand that “Chicken Grease” refers to a term that, according to ?uestlove and Genius, was used by Prince when he wanted his guitarist “to play a 9th minor chord while playing 16th notes.” You simply caught the funk and ran with it.

I won’t be one of those people who tries to act like you can’t find good music nowadays because that argument is, frankly, lazy.

But there’s a reason why 24 years later, Voodoo still maintains a grip on us.

I refer to Voodoo as an experience and not an “album” because that word would be an understatement. Anyone can organize a collection of audio recordings, slap a name on it, and distribute the collection under a chosen name.

But to craft an experience is to craft a conscious event in and of itself– an event that leaves a mark, increases one’s knowledge, and informs how one navigates the future. Experiences can be physical and spiritual, such as the sanctification D’Angelo witnessed as a child in the Pentecostal church or the birth of his son. And like love, Voodoo is representative of more than a mere word or feeling– it is an intense, tangible manifestation of selflessness. Of care and intention.

Voodoo is, in fact, love. Love for musicianship. Love for artistry. Love for Black music. And like Black music, Voodoo is transcendent of time and space and streaming numbers.

D’Angelo rocked the world not once, not twice, but three times via Brown Sugar (1995), Voodoo (2000) , and Black Messiah (2014). And while there’s no telling whether or not he’ll be curating any new experiences in the near future, he did bless us with an amazing track, called “I Want You Forever,” on The Book of Clarence soundtrack with Jay-Z.

Elusive as he seems, he is just a man. But even man can craft greatness. And though perfection can never truly be achieved, he got damn close with Voodoo.

Leave a comment