A deep dive into Black artistry and how Black musicians are the blueprint.

American music comprises a number of genres and distinct sounds, but they all have one thing in common. The rhythms, flows, and cadence are found in the fabric of the Black diaspora.

From the second enslaved Africans set their feet upon the shores of the Americas, music became an essential aspect of Black American culture. It was through music that they could trek through their arduous tasks. It was through music that they communicated with one another, signaling the best manners through which they could escape from their captors.

Music helped lead the feet in rhythm and from captivity, with enslaved Africans in the South cultivating hymns, spirituals, and field chants that would lay the foundations for Gospel Music and the Blues. Over time, these traditional sounds would meld with contemporary instruments and advanced technologies, devising what we now know as “Black Music.” But “Black Music” is more than Gospel and the Blues and Hip-Hop– American music is Black Music.

As is the case with most structures of the United States, the breakdown of musical genres in the early days of the music industry mirrored that of American society. The distinctions were largely determined by race and class. “Popular Music” was the leading genre, with “Race Music” –intended for Black folks– and “Hillbilly Music” –intended for poor white folks– following close behind. Race Music and Hillbilly Music often existed amongst other genres and subgenres, such as Ragtime and Folk, but the marketing model, like the country itself, “othered” all that wasn’t white and upper class.

William G. Roy speaks of this “othering,” particularly with regard to the origins of Folk Music, in his article entitled “Aesthetic Identity, Race, and American Folk Music.” Early Folk Music was regarded as “The Music of the Left,” associated most prominently with the Communist Party. But even “The People’s Music” eventually became associated with white people despite the genre’s potential to bridge racial gaps. Roy argues that the racial breakdown of musical genres is nearly inevitable, coming as a result of the cultural assets that are associated with a particular type of music. This leads to the construction of aesthetic identities and competition amongst now-racialized genres.

“The development of aesthetic identities is a social construction more than a matter of individual tastes,” Roy posits. “Moreover, the construction of genres often involves the erection of boundaries between groups.”

These boundaries, which are both social and cultural, lead to racial coding amongst musical genres. “This contrast between social and cultural boundaries created by promoting the music of a social ‘other’ means that the social identity and meaning of folk music is more plastic than other genres,” Roy said. “The boundaries among genres influence social boundaries less as a response to the vicissitudes of an autonomous cultural drift than from the willful action and interaction of identifiable groups.”

In essence, this means that people erect racialized, aesthetic identities within the music landscape to establish social boundaries and establish a hierarchy of “cultural capital,” which sets a standard for what type of music is seen as more valuable when compared to others. This also helps with marketing music to different demographics. Having a centralized look for a genre helps determine what strategies one must employ to both define the target audience and reach that audience effectively.

Yet, boundaries, labels, and racialized structures did not stop Race Music from both permeating and shaping the mainstream for generations to come.

Ragtime, a precursor to Jazz, was the premier form of Popular Music in the early 20th century. A form of African-American music that utilized syncopated rhythms and the banjo (an instrument created by enslaved Africans), popular Ragtime performers included Scott Joplin, the “King of Ragtime,” Tom Turpin, the “Father of St. Louis Ragtime,” and Winifred Atwell, a Trinidadian pianist who gained popularity in Australia and Britain. The success of Ragtime, Jazz, and the Blues established Black musical forms as a lucrative commodity and form of creative expression.

“Crazy Blues” by Mamie Smith especially changed the game. Released in 1920, this Blues record catapulted the singer into success, making her the first-ever Black woman pop singer. It also changed the industry’s understanding of how valuable Black talent could be. According to the Library of Congress, “Crazy Blues” sold 75,000 copies in the first two months, therein causing major record companies to consider Black people – the “other” – as a consumer-base worth producing mainstream records for.

Musical genres would continue to be associated with particular races, yet Black musicians were still able to obtain commercial success and interest. At the helm of Jazz, which was born in New Orleans, Black musicians took elements from Ragtime, added improvisation, and melded the traditional rhythms of their African ancestors. Cornet player Charles “Buddy” Bolden is regarded as the first-ever Jazz musician, but pianist Duke Ellington and trumpeter Louis Armstrong helped popularize the genre and put the culture on the map, with the latter musician being a progenitor of Swing. According to Carnegie Hall, Swing is characterized by its big band sound, “swinging” eighth notes, and a walking bass line. Though white clarinetist Benny Goodman is known as the “King of Swing,” Louis Armstrong’s swing-based style largely influenced other Jazz musicians and vocalists such as Billie Holiday, Bing Crosby, and Ella Fitzgerald.

From then on, Black musicians would continue cultivating new sounds that influenced musicians of all races. By the 1940s, the term “Race Music” would be replaced by “Rhythm and Blues (R&B).” As stated by the Library of Congress, R&B initially served as a sort of umbrella term to describe secular music that came from African-American artists. We understand it now to be a culmination of elements from Jazz, the Blues, and Gospel music. Soon after, in the mid 1950s, guitarist and singer Chuck Berry would pioneer Rock and Roll by utilizing elements from R&B and combining it with sharp guitar sounds and “musical devices characteristic of country-western music and the blues,” according to Brittanica. Although Jimmie Rodgers, a white singer and songwriter from Mississippi, is considered the “Father of Country Music,” it was Black musicians like guitarist Lesley “Esley” Riddle that helped shape the genre. Riddle was a large influence on The Carter Family, a group known as “The First Family of Country Music.” The impact of Black artistry was also seen in Country Music through the use of the banjo and melodies from hymns sung in Black southern churches.

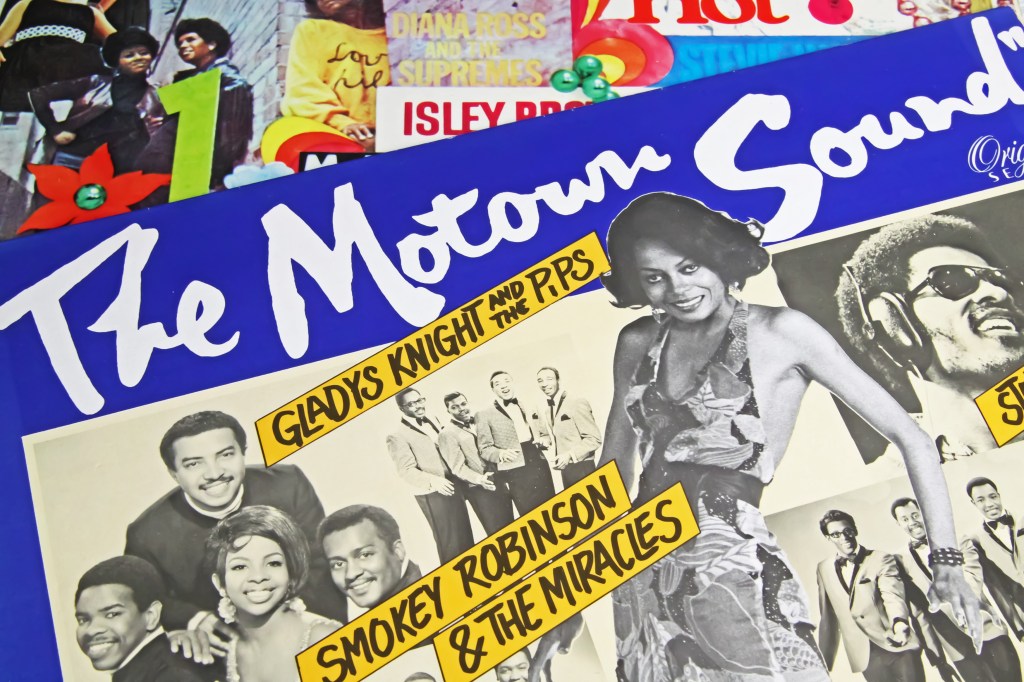

Ray Charles would later pioneer “Soul,” a sub-genre of R&B, with the 1959 release of “What’d I Say,” with artists such as Sam Cooke and Aretha Franklin– known as the King and Queen of Soul– and a slew of Motown Records signees perfecting the R&B/Soul sound throughout the 60s– Gladys Knight and The Pips, The Isley Brothers, Stevie Wonder, Tammi Terrell and The Supremes, to name a few. With the 70s we would see the rise of Disco music, a genre that, according to Britannica, was initially ignored by the radio yet heavily played by DJs in the underground club scene– clubs that catered to Black, Latino, and gay dancers. Disco had a mass appeal, but the music was performed mostly by Black entertainers, with people like Donna Summer and Gloria Gaynor crafting popular Disco hits.

Embed from Getty ImagesThe Disco craze would eventually die down, with events such as the Chicago-based “Disco Demolition Night” of 1979 representing a symbolic death of Disco. Many people– white Rock fans in particular– found themselves dismayed by Disco due to its so-called superficiality and linkage to queer culture. On this particular night, a crate full of Disco records was blown up at Comiskey Park, which is now the Guaranteed Rate Field. But from the “ashes” of Disco rose “House” music, a genre pioneered by Frankie Knuckles, an openly gay and Black DJ who popularized the genre in the underground Chicago club scene.

Around the same time, “Hip-Hop” would rise in the streets of New York City, with MCs from the Boogie Down Bronx to Queensbridge cultivating a culture that, to this day, dominates the American mainstream– Grandmaster Flash and The Furious Five, DJ Kool Herc, Juice Crew and Coke La Rock are a mere few of the many early day rappers and rap groups to lay this foundation.

The term “Popular Music” lends itself to any non-Folk music that was created to obtain commercial appeal. Though it was never intended to center Black musicians, they have leaned on the rhythms and legacies of their ancestors throughout history to cultivate what we know as American music– music that has transcended genre, geographical location, race, and life experience as a whole.

Oftentimes, when Black artists and groups choose to lean into seemingly-white genres– think Run-D.M.C’s rap-rock crossover in the 80s and Beyonce’s recent country singles– it is met with controversy when, in reality, these artists are reclaiming genres that their musical forefathers and mothers pioneered.

“Race Music” is a thing of the past in the sense that we no longer use this term, but sentiments regarding the labeling of Black music remain the same. When Black artists release music– music that often comprises multiple sounds and genres– it is almost always labeled as “R&B/Hip-Hop.” Even when Black artists make music that very clearly exists outside the confines of this label– music that has, over time, become associated with white musicians– it is labeled as though it is “inspired” by that genre rather than an actual part of it.

Not all Black people love House or Rock or Folk or Country music, but Black engagement with these genres and their accompanying cultures is far from a foreign concept. To see it as such undermines the legacy of Black artistry.

Black people have been exploited, oppressed, and spat upon on every level that has ever been conceived. But that has never stopped them from crafting amazing music. In fact, the turbulence that encompasses the Black experience has often been the motivating factor.

Black Music is the score to the so-called “United” States of America, a legacy that cannot be rewritten no matter how hard some try to do so. It has comprised a number of sounds and has, in some cases, been watered down to appeal to non-Black audiences. But one thing remains the same in spite of those who attempt to rewrite history.

You can never outdo, replace, or erase the blueprint.

Leave a comment